The dike as a landscape element takes on many shapes [1]. Depending on their form and location, dikes determine the ‘face’ of the Dutch polder landscape. Of course vegetation, land allotment and building development patterns also play an important role. Yet dikes are vital to the landscape’s appearance: apart from their form and location, their uninterruptedness defines spaces in a landscape and connects areas with each other. Dikes make differences in the polder landscape legible: a dike in a river landscape is different from one built in a sea-clay or peat landscape or the area around the IJsselmeer lake. Dikes therefore contribute to the identity and variety of the landscape. They simultaneously provide coherence, a sense of space and a rich variety of appearances. But how do you get a grip on the dikes’ spatial significance?

The seminal publication Het toekomstig landschap der Zuiderzeepolders (literally, ‘The future landscape of the Zuiderzee polders’ [1928]) provides some leads. In this manifesto of Dutch landscape architecture, planning experts such as D. Hudig and T. van Lohuizen described the importance of dikes as follows: ‘The dike is a significant element in every polder. Located on the border, it provides a view on one side of the landscape at its foot, unfolding its particular structure; on the other side it provides a view of the surrounding land, which often has a completely different character. The long, broad slope is one of the dike’s most beautiful features (. . .)’. From this, it can be inferred that a dike’s spatial significance depends on your vantage point, on the perspective you choose for reading and understanding dikes in the landscape. There are at least two different ways of looking at dikes: from the air and from the ground. In these vertical and horizontal perspectives features such as the dike’s course, cross-section and revetment always play a different role.

The course, cross-section and revetment of the dike exert great influence on its spatial significance. Plan for a new sea dike in the IJsselmeer area (Netherlands), Jacob van Hoorn, 1737 (source: TU Delft Library, Kaartencollectie Trésor TRL33.5.07)

The view from the air

You get a bird’s eye view of the dike system regardless of whether you view it from the air or on a map. It becomes clear that dikes form spatial patterns that endow the landscape with structure. They provide cohesion in the landscape and are also the interface between land and water, or between different polders that are enclosed as spatial units. Dikes ‘frame’ different types of landscape and landscape units. Like the black lines that separate the pictures in a comic book, the dikes are the green lines that demarcate the Dutch landscape. This also means that dikes are connecting structures: through cities and nature, they meander everywhere and connect the coast with the hinterland. This is significant, not only for plants and animals but also for humans.

Dike patterns also make the history of reclamation in the polder readable: in Friesland (NL), for example, you can see an intricate, irregular pattern of dikes and quays, an echo of the early individual reclamation that from the time of the Romans gradually developed into ring dikes; you can discern the haphazard process of diking accreted silted soil in Zeeland, and the systematic reclamation of the West-Frisian and Holland-Utrecht peat areas that started in the early Middle Ages. The ring dikes mark the areas of reclaimed land that have lain low in the landscape since the sixteenth century. Dike patterns are a record of the formative force of water and the way humans have dealt with it. Natural processes of sedimentation, erosion and stagnation through water provide the foundation for a rich variety of polder landscapes in the coastal, river and peat areas. Dikes also reflect technological progress, such as the Dutch Delta works, the Afsluitdijk (the enclosing dam of the IJsselmeer) and land reclamation in the IJsselmeer area. In a nutshell, the shape of a dike makes it possible to read how we have dealt with water: from the small-scale and winding in early times to the very large-scale and rectilinear today.

The development of the landscape expressed by the pattern of dikes, here visible on the island of Goeree Overflakkee (SW-Netherlands) (drawing by: Michiel Pouderoijen, TU Delft)

The view from the ground

Viewing the dike from the ground means you stand on or next to the dike or see it from a distance. Here, conditions affecting visual perception such as vantage point, the viewer’s elevation and viewing direction, movement, and the weather play an important role. The interplay between the dike’s sideways slope, structure and revetment determine its spatial significance at eye level.

In the field, dikes are spatial borders: they determine the form of the landscape, the two- and three-dimensional composition of vertical elements that define the landscape space. The composition determines the scale, proportion, orientation and significance of the space. Every dike has its own specific characteristics, with form creating the connection between a landscape’s history and our spatial experience. Apart from the sideways slope, the cross-section and revetment are also important. The dike cross-section describes the dike’s height, the angle of inclination of its slope, and the width of the crest and the toe. This is important because a high, steep dike creates a different spatial effect from, say, a gently sloping wide dike. Whereas a steep dike makes a spatial border palpable, a dike with a gentle slope tones it down. Whether a dike is revetted with stones or only with grass also plays a role. The revetment is an indication of the function and use of the dike’s inside and outside, and it can create visual continuity or, in fact, contrast. Trees reinforce the three-dimensional effect of the dike but due to technical considerations they cannot always be planted.

The dike as landscape balcony at Wörlitz, Dessau (Germany) (photo: S. Nijhuis, 2013)

Standing on a dike is like standing on a landscape balcony with sweeping views on either side – stretches of water or polder, or both. Movement plays an important role in how we experience these landscapes because there are often roads or cycle-paths on top of the dikes. Seen from the car or bicycle, aspects of the landscape succeed one another like a cinematic experience, as we float above the landscape. The straight or curved course of the dike then provides variation or calm and opens up perspectives on the landscape. Here, too, the cross-section strongly affects spatial experience: if the road and cycle-path are both located on the crest, for example, their width might diminish the special experience of the dike, whereas if the cycle-path is located on the dike’s flank more of the dike remains.

The dike’s continuity makes the landscape’s cohesion visible and connects the local with the supra-regional: in the Rhine-Meuse river area dikes follow the course of the rivers with occasional sharp bends around deep lakes that bear silent witness to past dike breaches; in the peat area dikes support a system of drainage lakes and cut through the low-lying polder land; in the coastal area dikes are like the layers of an onion, enfolding and merging the land as it grew; and the dikes in the young IJsselmeer polders and the ring dikes around the polders of reclaimed lakes make it possible to experience the former stretches of water as landscape spaces.

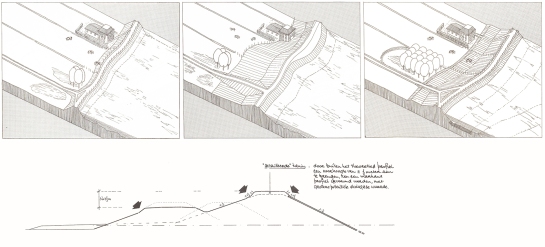

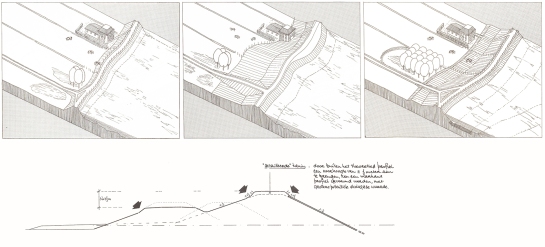

Research through design exploring spatial qualities of re-enforced river dikes (source: Y. Feddes & F. Halenbeek, 1988, compilation: S.Nijhuis)

In conclusion

Taken together, these ways of looking create a basis for approaching the dike from a spatial perspective and endowing it with aesthetic landscape qualities. Thus, if work is carried out on a dike attention must be paid not only to safety and multi-functionality but also to scenic beauty. Carefully designing a dike’s course, cross-section and revetment ensures its contribution to the identity, spatial aspect and variation of a landscape. The design disciplines are vital here: landscape architects and urban planners play a key role in planning developments that affect the landscape, and they should take the lead in developing the expertise and tools to formulate the dike as an object of spatial design in a context of functionality and social embedding.

Note:

[1] This text is published as: Nijhuis, S (2014). Dikes in focus. In EJ Pleijster & C van der Veeken (Eds.), Dutch dikes (pp. 72-75). Rotterdam: nai010 publishers. In Dutch: Nijhuis, S (2014). Oog voor de dijk. In EJ Pleijster & C van der Veeken (Eds.), Dijken van Nederland (pp. 72-75). Rotterdam: nai010 uitgevers. Both available at: http://www.nai010.com/dijkenvannederland